When I started to learn Chinese in 2000 I soon realized that just learning the sounds was not enough. Nor could you just learn the pinyin and expect to make sense of the language. You need to learn characters.

Once I learnt a few characters I was hooked, but if I ever picked up an actual publication in Chinese I was stuck. Each line had one or two new characters. In my small dictionary I searched for the characters, and each search took at least a minute and sometimes much more. Reading was getting easier but looking up characters was a limiting factor. I found many problems:

- Identifying the radical (sometimes obvious, but not always.)

- Looking through the long lists when the radical was very common (four hundred characters have 扌as their radical)

- Looking for characters with ‘hard-to-classify’ radicals

- Trying to find a character that was not even in my usual dictionary (How do you find something when it isn’t there!)

- Using a bigger dictionary meant more characters but then searches became slower, looking through 2600 pages!

What was frustrating was I couldn’t effectively use my acquired knowledge. I might recognize the ‘phonetic’ part of the character but I couldn’t search for that.

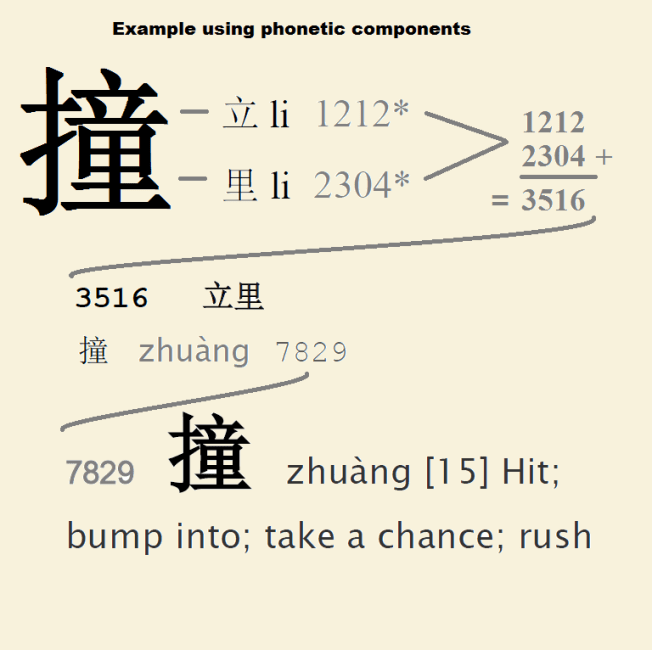

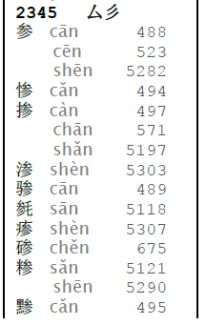

In 2010 I started working on a better way to find characters. I made a list of almost all the characters that can be written using a Windows-based computer and I broke them down into their components. Each component was given an index number. I made it so that you could add the index numbers together to search for a combination of two components. My theory was that as characters are normally comprised of combinations of components then it would be possible to break each character down to its components and then have an index that put the characters back together. Searching on any component or combination of components would make for much quicker and more reliable searches. For example, if you saw a character with a 廿 in it, you could look it up in this book but not in a normal dictionary. All those characters are listed together in Chinese by Numbers. There is no dictionary or mobile app that can do that. Suppose you are interested to know the variation in pronunciation of characters that contain 冖 and艹. This book gives a list and you quickly find that most are pronounced either láo or yíng. You can’t get that from any dictionary or app.

Then, in the body of the book, I identified which characters were most important and which were comparatively rare. Each entry shows this in the font size. A big font means an important character. This makes it very easy to use the book for study, concentrating on the most important characters. As I use this book I keep finding new useful features .

Once I had a printed draft of my book I quickly realized how good it was to have a reliable quick and thorough way to search for new characters. So I decided to publish and in the end chose self-publishing. I have had a great response from those who have used it, but reaching my market is difficult. I hope that if you are reading this and want to get a copy that you might use the links below:

http://www.amazon.com/Chinese-Numbers-ultimate-method-characters/dp/1922022241

http://www.bookdepository.com/Chinese-by-Numbers-David-Pearce/9781922022240

http://www.barnesandnoble.com/w/chinese-by-numbers-david-j-pearce/1110603411?ean=9781922022240

http://www.vividpublishing.com.au/chinesebynumbers/